fter years of public outcry and investigative pressure, the ground has finally broken at an Irish site long believed to conceal a disturbing legacy.

A long-awaited forensic excavation has begun at the site of a former mother and baby home in Tuam, County Galway, where the remains of nearly 800 babies and children are believed to be buried.

The institution, once operated by the Sisters of Bon Secours, served as a refuge for unmarried mothers and their children from 1925 until its closure in 1961.

The investigation follows a decade-long campaign by local historian Catherine Corless, whose research uncovered death records for 798 children.

Just two of these children are confirmed to have been buried in a cemetery. The rest, it is presumed, lie in the grounds of the former institution, many discarded in a disused sewage tank referred to by locals as “the pit.”

Ms. Corless told Sky News, “I’m feeling very relieved… It’s been a long, long journey. Not knowing what’s going to happen, if it’s just going to fall apart or if it’s really going to happen.”

Her discovery in 2014 shocked Ireland and the world, revealing the harsh treatment unmarried mothers and their children endured in a society deeply influenced by conservative Catholic values.

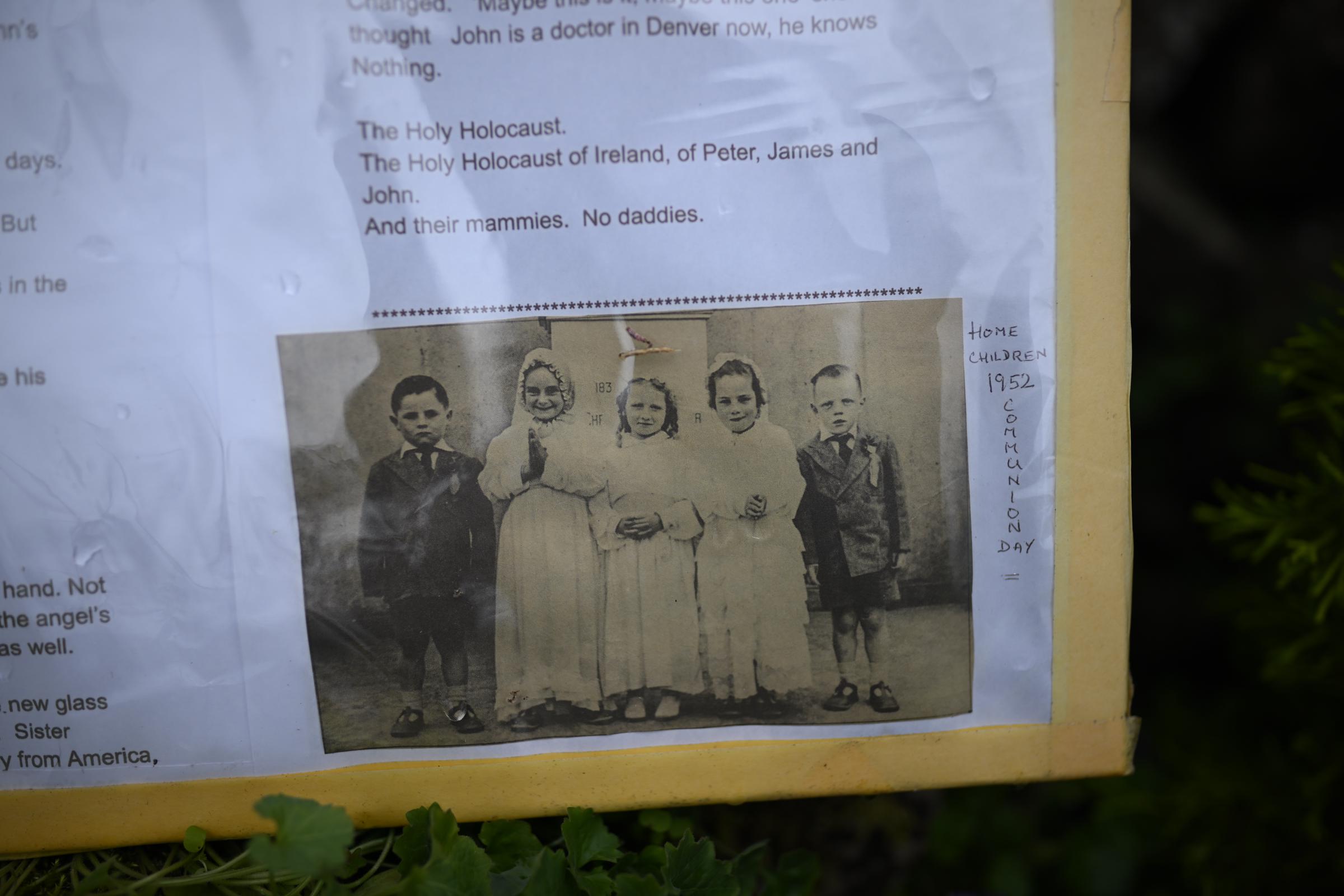

The children were considered “illegitimate” and denied the basic rights and dignity afforded to others. The mothers, often victims of rape, incest, or violence, were hidden away and subjected to strict regimes under the authority of nuns.

Ms. Corless noted that babies died almost every fortnight, which is why the burial site grew so large. The site was initially discovered in 1975 when two 12-year-old boys found bones in the septic tank.

At the time, the community believed the remains were from victims of the Irish famine in the 1840s. However, Ms. Corless later verified the truth by meticulously checking death certificates.

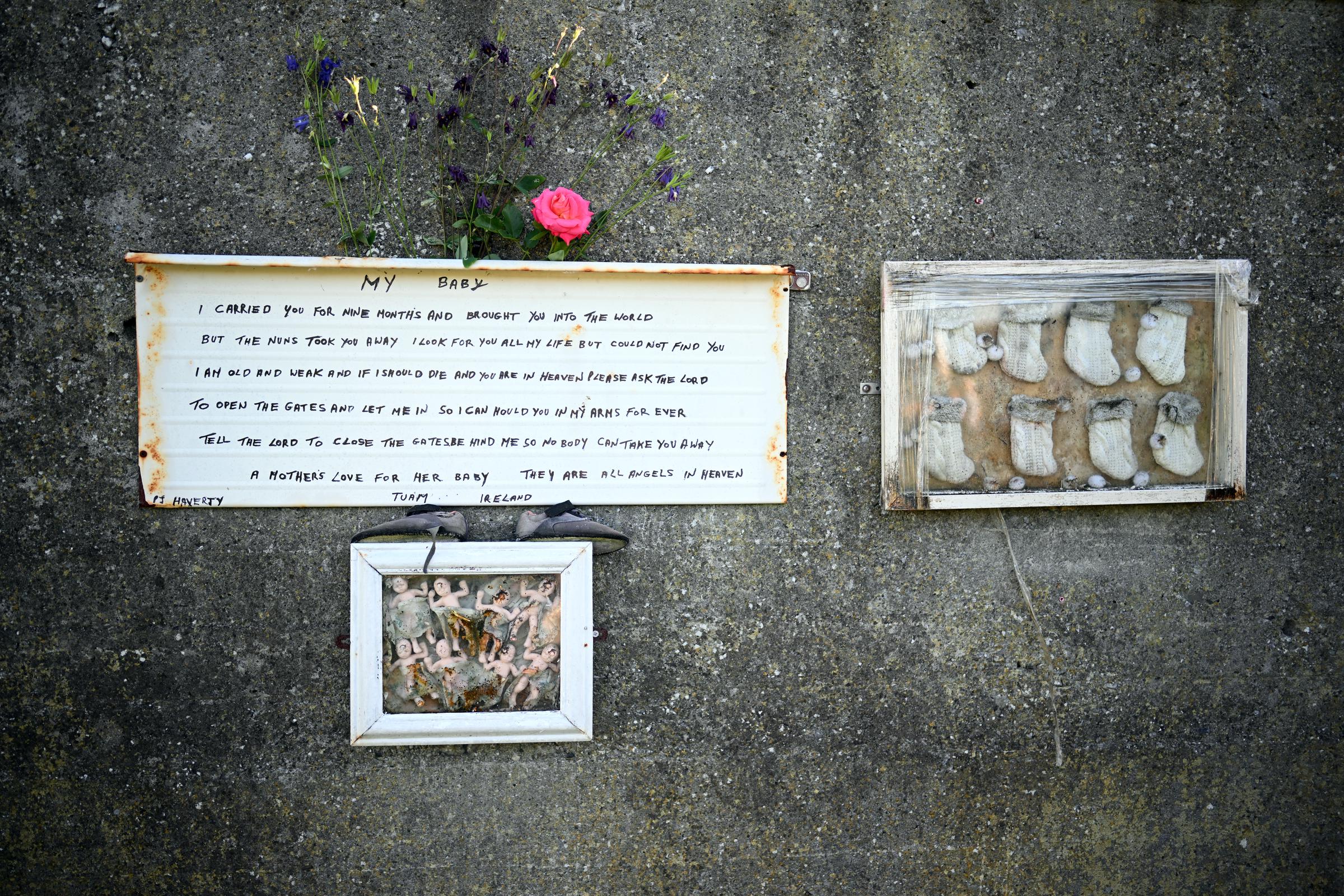

The death records list causes such as malnutrition, measles, and tuberculosis — diseases rampant in that era. These children were buried without coffins or headstones. The home was later demolished, but locals maintained the area with a plaque and a figure of the Virgin Mary.

Annette McKay, a woman now living in Manchester, is one of many hoping the excavation will provide answers. Her mother, Margaret “Maggie” O’Connor, gave birth to a baby girl named Mary Margaret at the Tuam home in 1942 after being raped at 17.

The child died six months later. McKay recounted that her mother was told of her daughter’s death while hanging laundry. A nun approached her from behind and said, “the child of your sin is dead.” Ms. McKay now hopes to reunite her late mother and sister in death.

“I don’t care if it’s a thimbleful, as they tell me there wouldn’t be much remains left; at six months old, it’s mainly cartilage more than bone. I don’t care if it’s a thimbleful for me to be able to pop Mary Margaret with Maggie. That’s fitting,” she expressed.

She also commented on the broader injustices committed at the home, stating, “We locked up victims of rape, we locked up victims of incest, we locked up victims of violence, we put them in laundries, we took their children, and we just handed them over to the Church to do what they wanted.”

She continued, “My mother worked heavily pregnant, cleaning floors and a nun passing kicked my mother in the stomach.” The Irish government issued a formal state apology in 2021 after an inquiry found that around 9,000 children died in 18 similar institutions.

Then Taoiseach Micheal Martin stated, “We had a completely warped attitude to sexuality and intimacy, and young mothers and their sons and daughters were forced to pay a terrible price for that dysfunction.”

The Sisters of Bon Secours admitted that the children were “buried in a disrespectful and unacceptable way” and issued a “profound apology,” offering financial compensation.

As the forensic team led by Daniel MacSweeney begins its work, there is a collective hope that dignity will finally be restored to the children who died there.

Ms. Corless remains haunted by the question of how a religious order, tasked with caring for the vulnerable, could treat children with such neglect.

“I’m still trying to figure that out,” she added. “I mean, these were a nursing congregation. The church preached to look after the vulnerable, the old and the orphaned, but they never included illegitimate children for some reason or another in their own psyche. I never, ever understand how they could do that to little babies, little toddlers. Beautiful little vulnerable children.”

The Tuam home is one of ten mother-and-baby institutions that existed in Ireland, which together housed approximately 35,000 unmarried women. Many of their children were forcibly adopted or segregated in schools.

Calls have been made over the years for a formal police inquiry and a state-funded memorial listing the names and ages of the 800 children believed to be buried at Tuam.

As excavation begins, the community and relatives of the deceased await closure. For them, the site at Tuam is no longer a hidden shame — it is a testament to a dark chapter in Ireland’s past that must never be forgotten.