Even if they weren’t intended to, there are some pictures that make you shudder. When taken out of context or examined through the prism of history, an innocent photo can take on an eerie quality. Why is it so unsettling? What is the backstory?

Cameras have recorded moments throughout history that evoke wonder, anxiety, and innumerable questions. These eerie pictures weren’t meant to be frightening, but they are memorable because of their enigmatic details or lost pasts.

Sometimes the tension is reduced when the truth about them is revealed, while other times the mystery is merely made more complex. Are you prepared to learn the tales behind these eerie historical snippets?

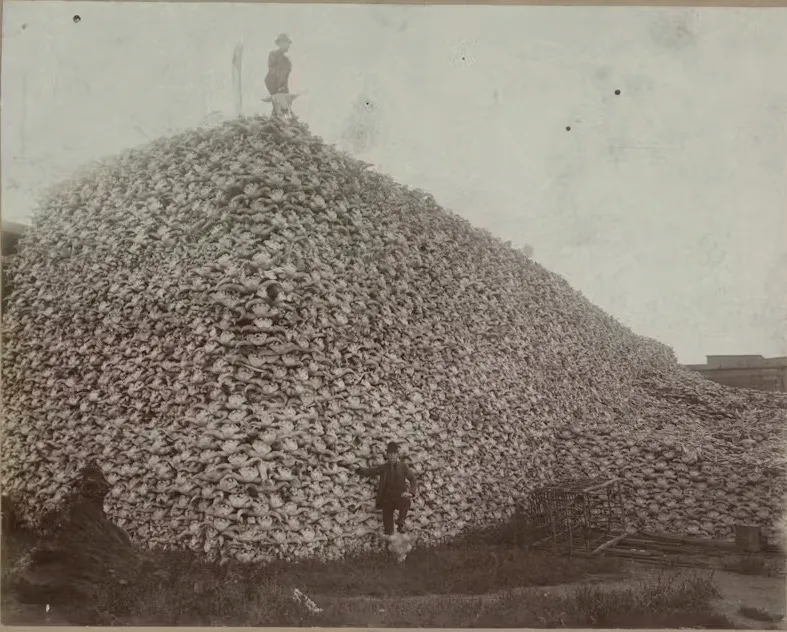

Bison skull mountain (1892)

Photographed in 1892 near the Michigan Carbon Works in Rougeville, Michigan, this eerie image documents a startling historical event. It displays a massive mountain of bison skulls that have been gathered for use in charcoal, fertiliser, and bone glue.

The tale this image conveys—not only “about the exploitation of natural resources but also about a” significant loss associated with colonisation “and industrialization”—is what makes it so disturbing.

Between 30 and “60 million bison lived in North America” around “the beginning of the 19th century”. That figure had fallen to an alarming 456 wild bison by the time this picture was shot.

The market demand for bison hides and bones, along with the westward migration of people, led to a ruthless massacre that wiped out the once-thriving herds. The majority of herds were exterminated between 1850 and the late 1870s, causing destruction to the environment and culture.

In addition to being a monument to corporate greed, the tall heap of bones in this image also symbolises the close bond that Indigenous Nations had with bison, which was violently broken by this widespread devastation.

Photographer Edward Burtynsky later referred to the bones as “manufactured landscapes” because they blur the distinction between natural and artificial landscapes, stacked like a man-made mountain.

Today, over 31,000 wild bison roam North America, thanks to conservation initiatives. This image is a sobering reminder of how nearly we lost them completely—a terrifying window into a history influenced by decisions that still have an impact on us today.

Bülow and Inger Jacobsen (1954)

At first sight, this image from the mid-1950s may appear a little unsettling, but it probably depicts a typical “day in the lives of Norwegian singer Inger Jacobsen and her husband, Danish ventriloquist Jackie Hein Bülow Jantzen”, famously known as Jackie Bülow.

As a well-liked vocalist in Norway, Jacobsen even competed for her nation in the 1962 Eurovision Song Contest. At a period when ventriloquism was flourishing, especially on radio and the new medium of television, Bülow entertained audiences with his distinct charm and skill.

The image looks to be a glimpse into a world that is very different from our own, a picture from a bygone era. Even though it is less prevalent now, ventriloquism hasn’t completely vanished. T

hree ventriloquists—”Terry Fator (2007), Paul Zerdin (2015), and Darci Lynne (2017)—even won America’s Got Talent, demonstrating the talent” and inventiveness of these entertainers. It’s evidence that some traditions endure in surprising ways even if the world may change.

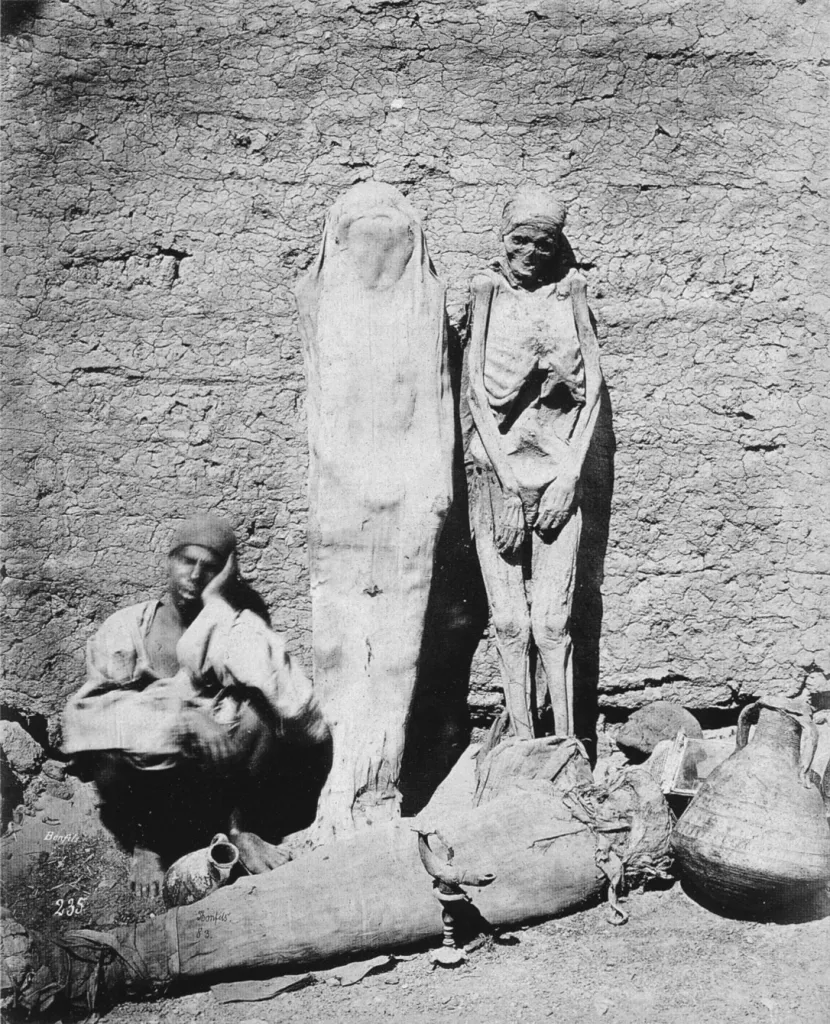

The dealer of sleeping mummies (1875)

Humans have long been captivated by mummies, and for more than 2,000 years, the mummies of ancient Egypt have captivated people’s imaginations. However, the history of their treatment tells an odd and occasionally disturbing tale.

Mummies were utilised in a variety of ways by Europeans during the Middle Ages, including being ground into powder to make purported therapeutic remedies, being made into torches because to their high burning efficiency, and even being used to heal conditions like coughs and broken bones.

This tendency was driven by the misconception that mummies were embalmed with healing bitumen, which was untrue. Mummies were no longer used medicinally by the 19th century, although people were still fascinated by them.

The desire for mummies was increased by grave robbers, and traders brought “them from Egypt to Europe and America, where” the wealthy valued them highly. They were utilised for study or displayed as status symbols. The “unwrapping party

,” which blurred the boundaries between science and entertainment in the 1800s, was one of the more odd traditions. “Mummies were ceremoniously unwrapped in front of” interested bystanders.

The way that these ancient artefacts were turned into commodities and used for “everything from medical tests to drawing-room spectacles” is demonstrated by this picture of a merchant relaxing amid a cache of mummies. It serves as a reminder of how cultural assets were handled in the past and the significance of their preservation in the present.

The lungs of iron (1953)

Polio was one of the most dreaded illnesses in the world before to vaccinations, paralysing or killing thousands of people annually. With almost 58,000 cases documented, almost 21,000 persons left disabled, and 3,145 deaths,

predominantly children, the 1952 outbreak was the worst in the United States. Instead of directly harming the lungs, polio damaged the spinal cord’s motor neurones, which cut off the brain’s connection to the breathing muscles.

“Being confined to an iron lung—a mechanical respirator” that forced air into their paralysed lungs—was frequently necessary for the sickest patients to survive. Children battling for their lives were held in rows upon rows of these tall, cylindrical machines in hospitals.

The terrible effects of polio are encapsulated in a single picture of these “mechanical lungs,” a terrifying reminder of the anxiety and uncertainty that engulfed families prior to the introduction of the vaccine in 1955.

.

Life was never the same, even for those who survived the iron lung, and they frequently suffered from long-lasting impairments. However, the image above, which shows unending rows of iron lungs, is a tribute to the epidemic’s human cost as well as the tenacity of those who battled to defeat it.

A dead infant and a young mother (1901)

In addition to capturing a poignant moment of sadness, the eerie picture of Otylia Januszewska clutching her recently departed son, Aleksander, also alludes to the Victorian practice of post-mortem photography.

This custom, which became well-liked in the middle of the 19th century, was a means of paying respect to the dead and maintaining a last, physical link to cherished ones, particularly in situations where the thought of dying seemed too much to handle.

The idea of contemplating mortality has ancient historical roots and is rooted in the concept of memento mori, which means “remember you must die.” Paintings representing death were common in the Middle Ages, and skeleton-themed items from older cultures provided a sobering but essential recognition of the frailty of life.

When photography first appeared in the 19th century, it was the ideal medium for creating intimate and personal reflections. With the advent of photography,

families would try to preserve their departed loved ones by photographing them so that their faces would always be accessible. In addition to allowing the living to grieve, it also helped them form enduring bonds and a sense of connection that endures beyond death.

It’s interesting to note that when a loved one dies these days, we usually concentrate on honouring their life rather than facing

the terrible truth of their passing—almost as if it’s frowned upon to bring it up openly. Victorians, on the other hand, welcomed death with enthusiasm and incorporated it into ceremonies that recognised its unavoidable existence.

A major component of that was post-mortem photography, which peaked in the 1860s and 1970s. Even though not all Victorians felt comfortable taking pictures of the deceased, the practice gained popularity, particularly in the UK, USA, and Europe, after photography was invented in the 1840s.

Maine industrial worker, age 9 (1911)

For many American working-class families in 1911, life consisted of putting in long hours, working hard, and finding any way to make ends meet.

“A 9-year-old girl from Perry, Maine named Nan de Gallant saw summers as an opportunity to work at the Seacoast Canning Co. in Eastport, Maine. She was working long hours with her mother and two sisters, helping her family haul sardines, rather than playing with friends or running through fields”.

Unfortunately, child labour was widespread in America in the early 20th century, particularly in sectors like agriculture, textiles, and canning. Every additional set of hands was helpful to families. But it meant giving up childhood for children like Nan.

She began working at the age of nine, which was regrettably not out of the ordinary for kids in her age range at the time. 18% of children aged 10 to 15 were employed in 1910, according to the US Bureau of Labour Statistics.

A legislation that prohibited children under the age of 12 from working in manufacturing was in effect in Maine, but it did not apply to the canning industry,

which produced perishable goods. Although the law was amended in 1911, it’s difficult to tell how much of an influence it had on Nan and other children.

In 1964, James Brock poured acid into the pool.

In order to stop black swimmers from accessing the Monson Motor Lodge pool, Motel Manager James Brock was shown in a terrifying photograph in 1964 pouring muriatic acid into it.

This action came when a group of black activists in St. Augustine, Florida, tried to integrate the segregated area. Brock made the decision to destroy the pool rather than permit equality.

Charles Moore’s photograph represents the bravery of individuals battling for civil rights as well as the pervasive bigotry of the day.

It reminds us of how far we’ve come and how far we still have to go in the struggle for equality. It teaches us the value of resiliency, the strength of defiance, and the necessity of facing up to painful historical realities.

Miners of coal coming back from the depths (C.1900)

Belgian coal miners endured arduous underground labour in hazardous conditions to support the burgeoning industrial revolution in the early 1920s.

They would cram themselves into a packed lift after hours of exhausting work in the dark, finally making their way to daylight. How much they depended on one another to get through it was evident from the lift’s creaking sound and the soft murmur of their voices.

Their features, smeared with coal dust, spoke of sacrifice and toil. Their pleasure in their work was evident in every crease and wrinkle, but it also revealed the toll the job took on them. Even at the expense of their health and safety, these men drove the industries that kept the world turning.

It served as a sharp reminder of the contrast between the mines’ darkness and the light above when they eventually emerged into the daylight.

More significantly, though, it served as a reminder of their fortitude and tenacity. Together, they continued because they had each other.

The core of their community was their camaraderie, which was formed via shared struggles; they overcame obstacles together, no matter what.

The fingertips of Alvin Karpis (1936)

Alvin “Creepy” Karpis was a prominent criminal from the 1930s who participated in high-profile kidnappings as a member of the Barker gang. He attempted to hide his identity when his fingerprints were found at two significant crimes in 1933.

In 1934, Chicago underworld physician Joseph “Doc” Moran performed cosmetic surgery on him and fellow gang member Fred Barker.

Moran changed their mouths, chins, and noses. He even used cocaine to freeze their fingers so that their fingerprints could be scraped off.

Despite these attempts, Karpis was apprehended in New Orleans in 1936, given a life sentence, and imprisoned for more than 30 years, including time at Alcatraz. In 1969, he was granted parole.

1930s Halloween costumes

Communities started establishing customs like giving away candy, throwing costume parties, and setting up haunted homes to deter disruptive behaviour during the Great Depression as violence and vandalism rose. Additionally, children’s costume options increased throughout this time, making the festivities more enjoyable.

A death mask being made by two guys (c. 1908)

The use of death masks to maintain the deceased’s likeness has been around for a while. For instance, the ancient Egyptians made intricate masks to aid the deceased in navigating the afterlife. The foundation for later death masks was laid by the statues and busts of their forefathers made by the ancient Greeks and Romans.

The emphasis on realism in death masks distinguished them from other representations. These masks were intended to create a permanent homage by capturing the individual’s actual features, as opposed to idealised sculptures.

Death masks were created for famous people like Napoleon, Lincoln, and Washington, and these were subsequently utilised for statues and busts that immortalised them for a very long time.