Robert and Shelly Battista had pictured a full house and a growing family. Their first child had just arrived, and life was beginning to settle into place when Shelly noticed something that didn’t feel right. What followed was the kind of news that redraws every plan.

When Shelly Battista noticed a lump while pumping at work, cancer was the last thing on her mind. She was 34, healthy, and navigating new motherhood. But what began as a suspected clogged duct soon unraveled into a hard-to-treat disease that would push her body and her dreams to the brink.

As she prepared for treatment, doctors moved quickly to save her life while trying to preserve her fertility. Within weeks, her ovaries were removed, and her chances of carrying another child seemed lost. Yet two years later, on the anniversary of being declared cancer-free, she delivered identical twin girls.

A Missed Signal, a Rushed Decision

Shelly had barely returned to the rhythms of working motherhood when something changed. It was February 2020, and while pumping at the office, she felt a lump in her breast. She chalked it up to a clogged duct, common among nursing mothers, and kept going.

But the lump stayed. And as weeks passed, so did the window for early intervention. Shelly had no family history of breast cancer. No known genetic risk. And with the COVID-19 pandemic disrupting routine appointments, her evaluation was delayed.

It wasn’t until May, three months after she first felt the lump, that she was formally diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer. She was caring for a six-month-old, and suddenly facing a type of cancer known to move fast and hit hard.

“We were just starting our life together,” her husband, Robert Battista, later recalled. “And we get this shocking news.”

What Shelly Was Up Against: The Nature of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

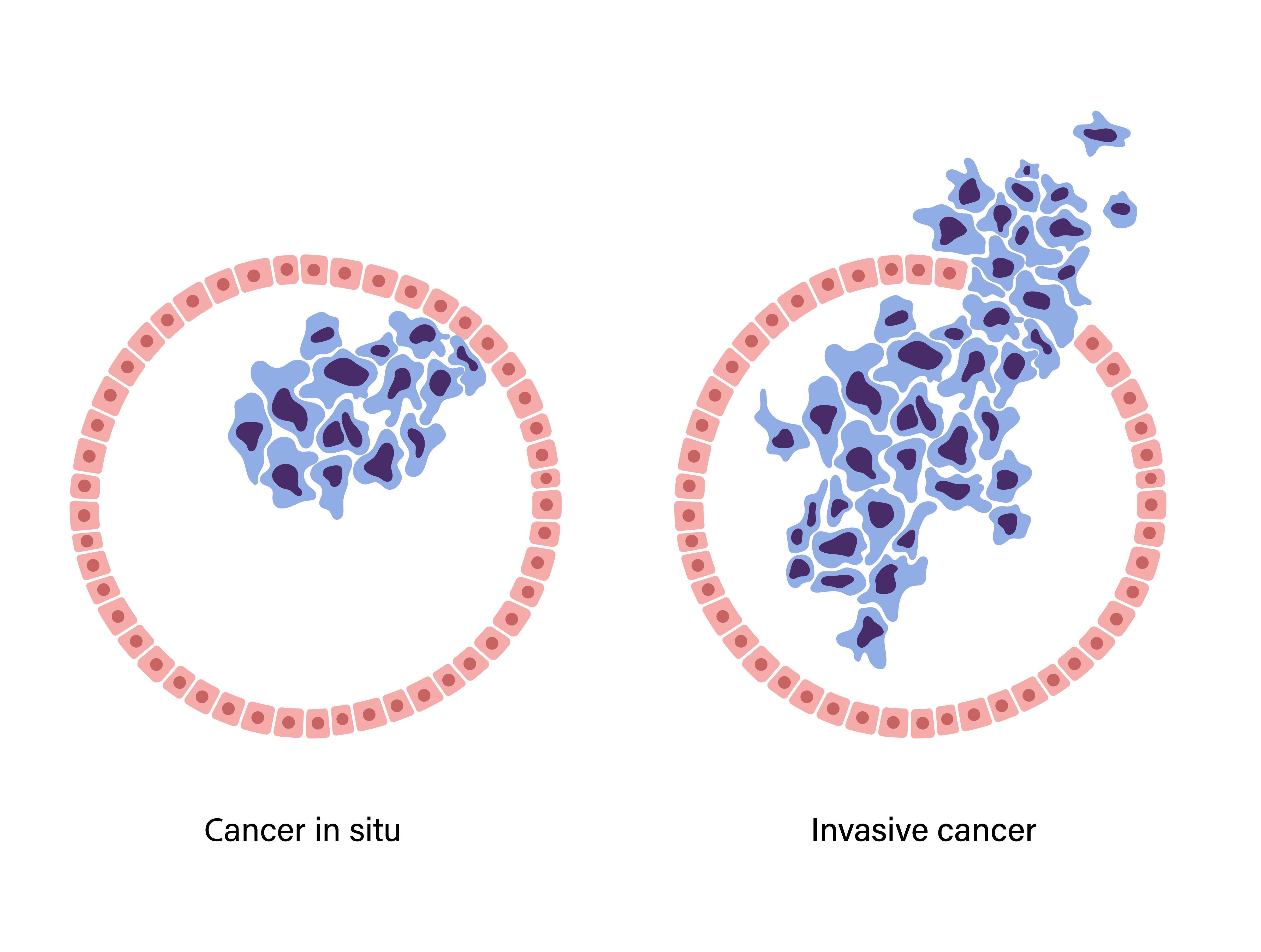

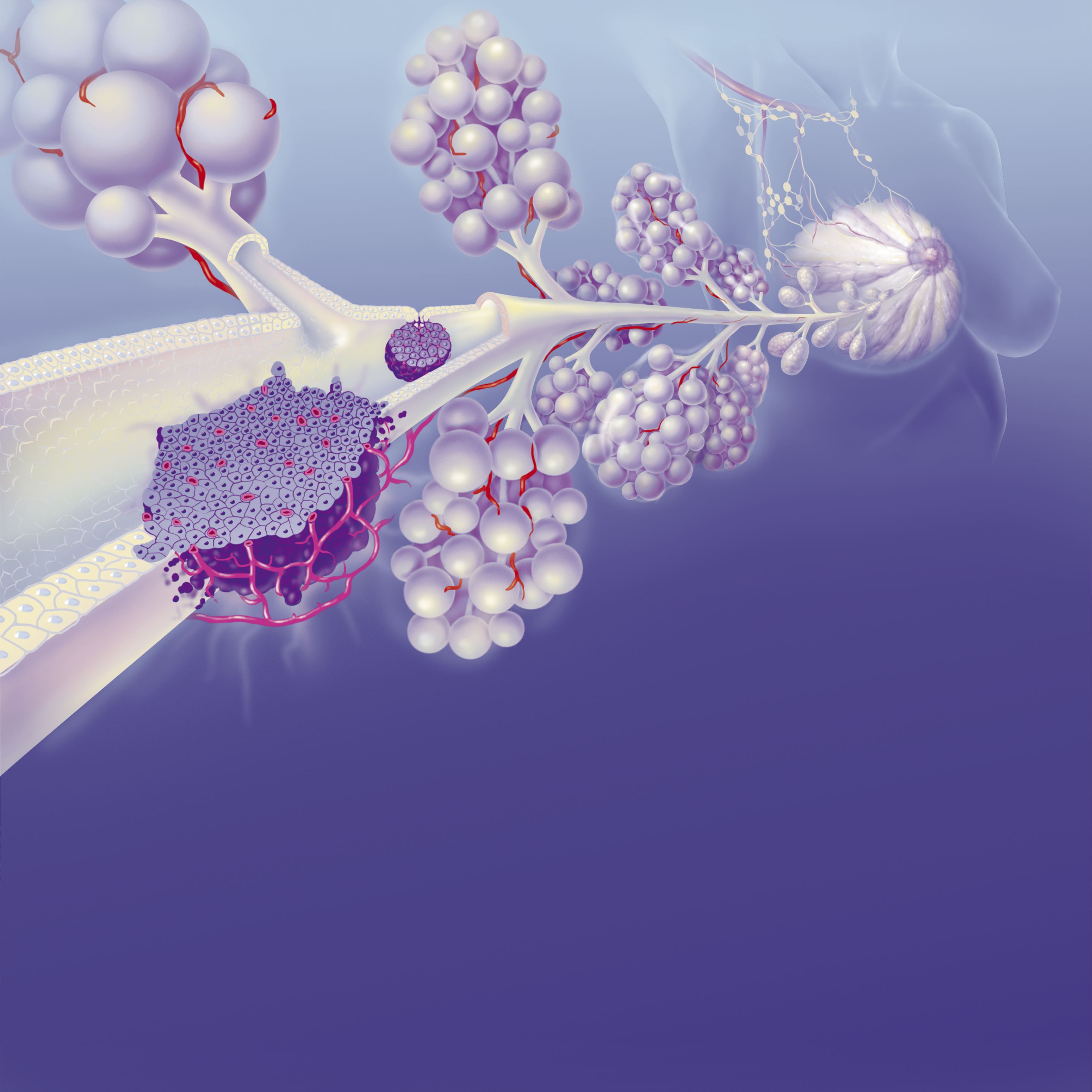

The diagnosis was triple-negative breast cancer, or TNBC, a rare but aggressive form of the disease. It accounts for a small percentage of breast cancer cases but carries disproportionate risk, especially for younger patients. TNBC lacks the three receptors — estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 — that most treatments target to block tumor growth.

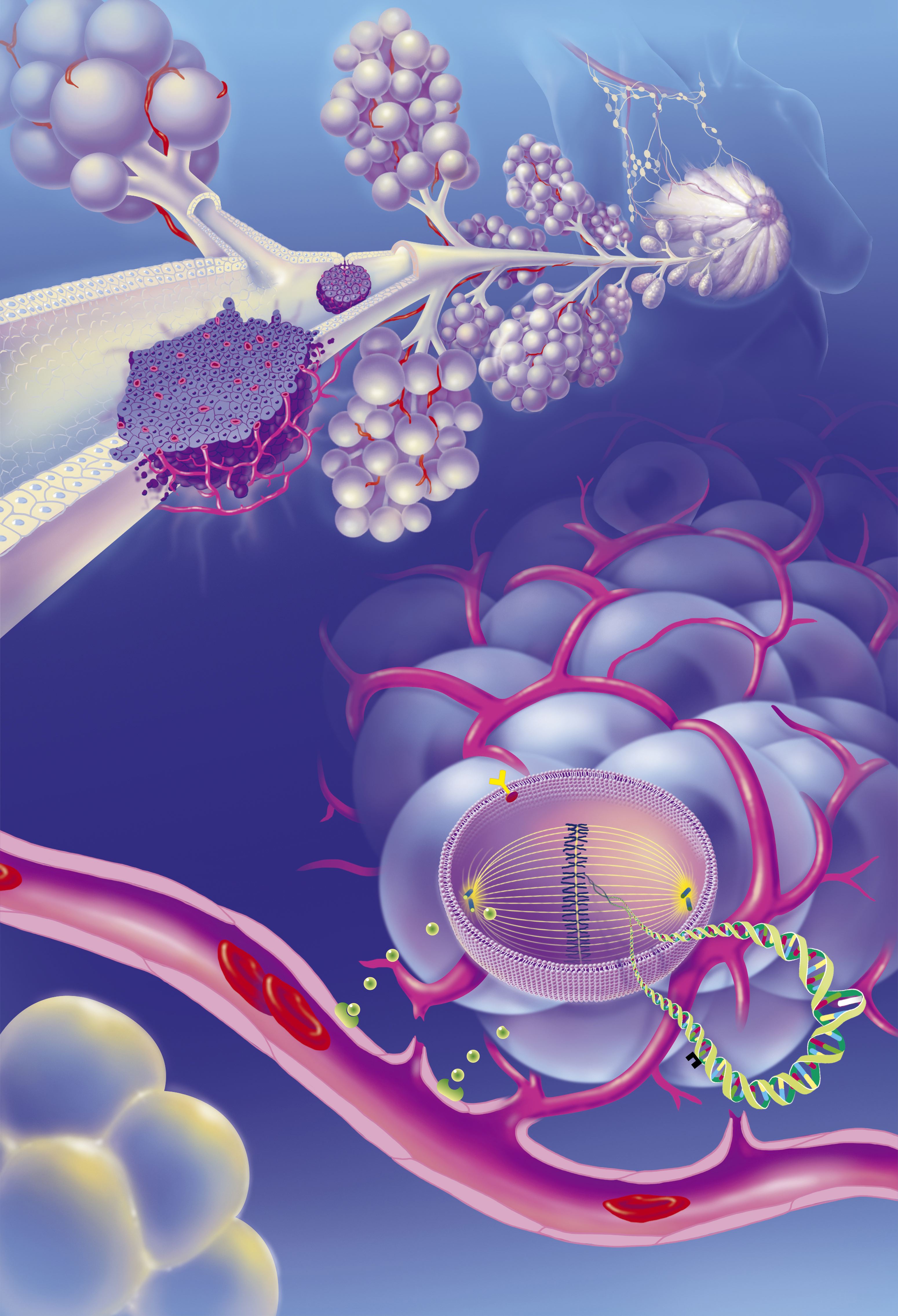

Without those biological entry points, chemotherapy becomes the only effective course of action. Chemotherapy, though necessary, is harsh. In women of reproductive age, it can quickly damage the ovaries, reducing hormone production and egg reserves.

For some, this results in temporary menopause; for others, the loss of fertility is permanent. The impact is more than physical — it removes future options before a patient has even had time to process her diagnosis.

Adding to the complexity is TNBC’s association with inherited gene mutations, particularly BRCA1 and BRCA2. These mutations not only increase the likelihood of breast cancer but also sharply raise the risk of ovarian cancer.

The symptoms of TNBC can vary and often resemble normal postpartum changes. They include a new lump or mass in the breast, pain in the breast or nipple, nipple discharge, a nipple that turns inward, skin dimpling, or skin that becomes dry, flaking, red, or thickened.

Swelling in all or part of the breast and swollen lymph nodes under the arm or near the collarbone may also occur. Though not all of these signs indicate cancer, any persistent change should be assessed by a healthcare provider. Routine mammograms remain an essential tool in early detection, often before symptoms appear.

Shelly’s diagnosis came with an added complication. Genetic testing revealed she carried mutations that sharply increased her risk of ovarian cancer. Her doctors recommended removing both ovaries and fallopian tubes once chemotherapy was complete, a precaution meant to reduce her future cancer risk, but one that would also make it impossible to conceive naturally.

If caught early enough, and if a patient is well enough to proceed, doctors can begin hormone stimulation to retrieve eggs for freezing. The treatment plan was medically sound. But it would come at a cost. And if Shelly wanted any chance of having more children, she had to act fast before chemotherapy began.

Knowing the couple wanted more children, Dr. Kara Goldman, a reproductive endocrinologist and medical director of fertility preservation at Northwestern Fertility and Reproductive Medicine, intervened immediately.

The window was narrow. Any delay in starting cancer treatment carries risk. But without fertility preservation, the chance of having more children would be nearly gone. Two days after her diagnosis, Shelly began fertility preservation.

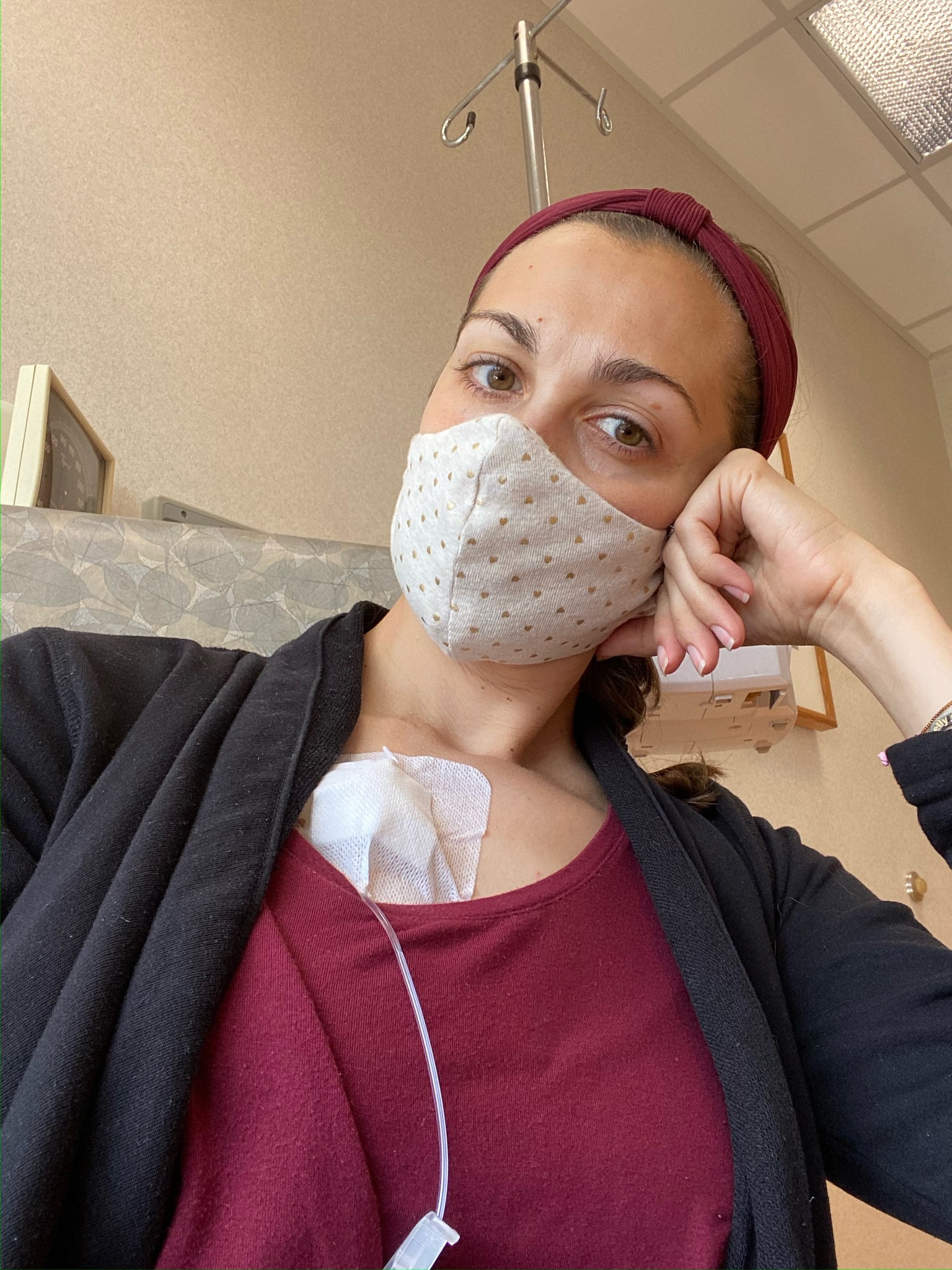

Under the guidance of Dr. Goldman, she started hormone injections to stimulate her ovaries, a necessary first step to retrieve mature eggs. Over the next two weeks, her body was closely monitored through bloodwork and ultrasound imaging.

Despite the emotional strain and the physical toll, the process moved quickly. There was no time to spare. At the end of the cycle, doctors retrieved and froze eight embryos. Only after the embryos were safely frozen did she begin cancer treatment.

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and the End of Natural Fertility

Shelly’s treatment began immediately after her fertility preservation cycle was complete. The first phase: 12 rounds of chemotherapy, each one aimed at slowing the cancer’s spread, each one pushing her body further from the life it had just created months earlier.

As the weeks went on, she began preparing for surgery. A double mastectomy was the next step, standard for patients with triple-negative breast cancer, especially those with BRCA gene mutations. Shelly didn’t hesitate. The priority was survival.

But the emotional weight of what was being taken from her — her breasts, her strength, and soon, her reproductive future — was never far behind. The cancer responded to treatment, but doctors remained concerned about her elevated genetic risk for ovarian cancer.

To protect her long term, they advised a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: the surgical removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes. By the time she completed treatment, Shelly no longer had the organs required to conceive a child.

Her uterus remained intact, but her ovaries, once stimulated to produce the embryos she’d frozen just weeks earlier, were gone. However, she’d done everything she could to preserve what was possible. The embryos were waiting. She was cancer-free.

Rebuilding Possibility: Pregnancy Without Ovaries

One year after completing treatment, Shelly was ready to try. “The ovaries and the uterus function very independently of each other,” explained Dr. Goldman, Shelly’s fertility specialist. In cases like this, hormone replacement therapy can prepare the uterus for pregnancy.

“Because she did not have ovaries producing hormones,” Dr. Goldman added, “we were able to provide her the hormones necessary for pregnancy.”

The first two embryo transfers didn’t work. Each failed attempt brought disappointment but not defeat. On the third try, Shelly received a call directly from Dr. Goldman. The embryo had implanted. She was pregnant. “We were both ecstatic and crying and yelling,” Shelly recalled.

For Robert, the news was more than just relief. “It was just awesome. We were going to have another kid, Shelly’s healthy, everything was behind us at that point,” he stated. But what came next was something they hadn’t planned for.

A Rare Twin Pregnancy and the Day Everything Came Full Circle

Following a successful embryo transfer, Shelly returned for a routine ultrasound. The transfer had involved one embryo, selected from the eight frozen prior to her chemotherapy. But the scan revealed an unexpected result: identical twins.

The embryo had divided after implantation, a phenomenon that occurs in approximately 1 percent of cases, according to Dr. Goldman. There was no intervention, no fertility technique designed to increase the odds of multiples. It had happened on its own.

Despite her medical history, her pregnancy went smoothly. Her uterus responded well to the carefully timed hormone support. No complications. No setbacks. Only waiting and counting down the days. Shelly was scheduled for induction at Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women’s Hospital.

The date set was December 9, 2022, exactly two years after she had completed treatment and been declared cancer-free. That coincidence had not been planned by the medical team. But for the new parents, it added a personal significance to a clinical milestone. Their daughters, Nina and Margot, were born that day.

“Despite a breast cancer diagnosis, chemotherapy, and losing both ovaries, Shelly’s dream of having three children came true,” Dr. Goldman later stated. “One perfect embryo, frozen urgently before chemotherapy, became two beautiful baby girls.”

“It’s a true miracle,” Shelly said. “We have two babies, exactly two years cancer-free. My heart is very full.” Months after the twins’ birth, Shelly appeared on the “Today Show,” where she reflected on life after cancer and childbirth.

“Lots of laughs, lots of cries and lots of laundry,” she described her day-to-day life. “It’s chaotic, but it’s perfect.” At the time, she and Robert were adjusting to life with three children, Emelia, Nina, and Margot. The story of their family’s journey drew widespread response online.

On Instagram, users flooded the comments section with support and emotion. “Congrats! What a beautiful story. You are a strong mama,” one person wrote.

Another commented, “Congratulations…what a blessing,” while one reacted simply with, “Awesome!!!” Another added, “What a wonderful story!!” One called her a “warrior mama” and added, “Congratulations!”